African agriculture is one of the most misunderstood ecosystems, especially by investors and development organizations. There is a persistent tendency to force smallholder farmers into contract agreements when most of them have made up their mind about the pros and cons of such agreements. While informal markets continue to carry the day, investors, development actors and policy makers continue to cling onto out-dated contract farming models which condemn smallholder farmers into labourers.

More than just supply and demand

While formal institutions still believe in the laws of supply and demand, such laws no longer call the shots in African food systems where borders no longer exist. Although commodity supply is important, profitability and sustainability result from many elusive factors. Part of the solution is careful characterization of the market and its actors. With the majority of smallholder farmers in developing countries shunning contract arrangements, unless when blackmailed through free inputs, informal markets are setting the rules of the game at different levels.

Farmers and vendors who exchange goods and knowledge in informal markets understand each other very well to the extent of getting into win-win pre-financing arrangements. This is contrary to views from some development actors which pretend to protect farmers from ‘middlemen’ when they will be destroying hard-earned relationships that must continue to exist when donor life-support has disappeared.

The biggest group of buyers for farmers who sell in the farmers’ market are vendors who buy in small quantities for selling further in high density areas. A second cluster of buyers are traders with permanent stalls who have invested into trading particular commodities. Traders purchase in bulk and often deal directly with farming communities. Measurements used in farmers’ markets signify the character of the market. When commodities come into the farmers market, they are in large measurements such as cardboard boxes, large plastic boxes (sandaks), 50kg bags and 20 litre tins for commodities ranging from butternuts and groundnuts to tomatoes. These measurements define the role of the market.

The fluid nature of informal food markets

While agricultural commodities come in bulk from farming areas, most buyers do not buy in bulk but in smaller measurements. This means the market uses different measurements to break bulk. All these nuances have a bearing on financing agricultural production. Where buyers bring commodities straight from production areas into the market, such volumes are stocked in the wholesale market for other informal or formal markets like processors.

The market pulls together a food basket from diverse farming areas. As it breaks bulk it mixes and matches commodities according to diverse nutritional needs. Individual buyers come to the market looking for specific food baskets which the market brings together. However, buyers rarely spend their whole budgets on single commodities. When commodities travel in bulk from one large urban market to another, the market where they travel to is responsible for consolidating food baskets for local consumers.

This fluid role needs to be understood as it influences consumption patterns. For instance, when the consumer budget gets strained, some commodities are rejected. That is how commodities are given weights in terms of whether they are necessities or luxuries. Commodities like lettuce, carrots, peas and fine beans are normally not produced in large quantities because they are sometimes considered luxuries not necessities. A necessity is hardly substituted fully and that is why a tomato is always in the market because it is a necessity. It has a marked price range. For commodities that are considered necessities, when demand is high, prices also tend to be high due to a built-in tendency by consumers to acquire appetites and tastes for particular commodities.

Significance of characterizing markets

Instead of focusing entirely on price, farmers and other value chain actors can benefit from characterizing and scoring markets in terms of availability, volumes absorbed by a particular market, commodity uses and price elasticity. Farmers markets can be high on price but score low because prices can fall below contract prices. On the other hand, while in contract arrangements the buyer and price can be known before producing, the informal market can be always available and sometimes offering better prices due to competitive pressures.

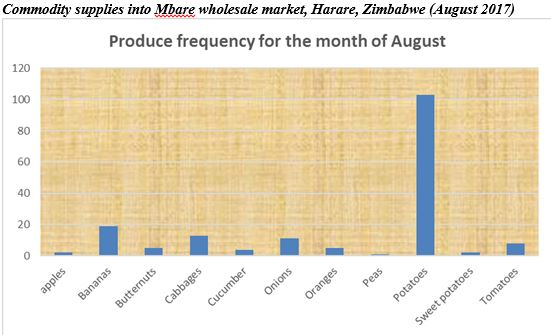

Knowledge already exists at different value chain nodes such as producer levels and market level. How can this knowledge be pulled together to inform agribusiness models? Processors and SMEs have raw knowledge still to be understood. If that knowledge is supported by that from the production side, it can become a bridge for resuscitating formal processing companies. Tracking volumes into markets also provides a framework for building consumption patterns in ways that speak fluently to prices. Commodities cannot be compared in isolation but in competition with each other. For the past six months, which 11 commodities were moving together and competing in the market and which one, upon entering the market, disturbed a necessity like tomatoes?

charles@knowledgetransafrica.com / charles@emkambo.co.zw / info@knowledgetransafrica.com

Website: www.emkambo.co.zw / www.knowledgetransafrica.com

eMkambo Call Centre: 0771 859000-5/ 0716 331140-5 / 0739 866 343-6